Connect with the author

Congress has failed to agree on a federal deficit reduction plan in part because the two parties are miles apart on taxes. Democrats insist on a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, while Republicans want only spending cuts. Could there be a way to break the logjam and let both sides declare victory? We suggest that the key could lie in reducing “tax expenditures,” subsidies run through the tax code. Government would shrink and distort economic incentives less, which should please conservatives, while liberals would applaud a fairer tax code.

How U.S. Tax Expenditures Work

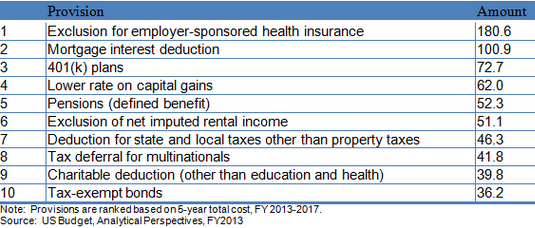

Public finance experts have long recognized that many spending programs are run through the tax code – typically delivered via tax credits, deductions, or exclusions from income. As the following list shows, the biggest subsidies go to homeowners making mortgage interest payments and employees who receive health insurance at work. But there are other big ones as well. Repealing or curtailing some of those subsidies would simultaneously increase tax revenues and cut federal government spending.

Largest Income Tax Expenditures in 2013 (in Billions of Dollars)

Some critics object to the notion that letting taxpayers keep more of their own money could be construed as spending. But most economists understand that direct spending and tax breaks can have nearly identical effects on the budget, resource allocation, relative prices, and the distribution of income. The principal difference is who administers the program and does the accounting. The late David Bradford famously illustrated this point by proposing, with tongue firmly in cheek, a Weapons Supply Tax Credit, which would allow arms manufacturers to sell their ordinance to the Pentagon in exchange for tax credits rather than cash. Instantly, the Defense Department’s budget would decline and tax revenues would fall by a similar amount. Yet government would be doing exactly the same thing – albeit even less efficiently.

Tax expenditures are mostly hidden from public view. Lawmakers can slip innocuous sounding provisions into the law that most Americans would reject if they understood their inefficiency or unfairness. In addition, the cost of tax expenditures tends to be downplayed. A new tax credit or deduction is considered a “tax cut” and thus avoids the “tax and spend” critique that would apply to a similar spending program. This creates a bias in favor of tax expenditures over traditional spending – even though they have similar budgetary effects. Not surprisingly, the sheer number of tax expenditure measures has increased sharply in recent decades.

Toward Greater Efficiency and Fairness

So far, we’ve emphasized that reducing tax expenditures could make government smaller and more efficient, an argument that would seem to appeal to Republicans. But there is also an argument that could appeal to Democrats. With the exception of “refundable” tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, which gives low-wage workers a refund beyond what they owe in income taxes, most tax subsidies pad the wallets of higher-income Americans. Tax expenditures reduced tax liability by an estimated 13.5 percent of income for taxpayers in the top one percent, compared to less than seven percent for households with low or moderate incomes.

At a time when budget cutters in Washington DC are looking for savings in safety net programs like Food Stamps and Medicaid, tax expenditures also should be on the table. Much federal money could be saved through cut backs in upper-middle-class tax entitlements like the mortgage interest deduction and tax-free employer health insurance. There’s also an argument for cutting tax breaks for wealthy investors, although the near consensus among tax policy experts breaks down there.

In the final analysis, a reasonable plan to restructure the federal budget and tame the debt must consider the effects on economic growth. Simply raising existing tax rates could harm the economy. In contrast, many experts argue that “broadening the base” – that is, eliminating or curtailing tax expenditures – could raise additional revenue while making the tax collection system as a whole simpler and more efficient. As a start in that process, the budget should explicitly recognize that many tax breaks are spending in disguise, account for them as such, and put them under the shared jurisdiction of spending and tax-writing committees. Shedding light on these stealth spending programs might make politics less secretive and rancorous, too.

Curtailing tax expenditures will not be politically easy – precisely because so many powerful special interests have a stake in them, and because the chief beneficiaries are higher-income Americans who know how to defend their interests in Congress and national politics. But if budget reformers can figure out a way to curtail many of these complex and hidden tax breaks, they could move the United States toward a tax system that is simpler, fairer, and more efficient. That combination might, just might, attract support across the current partisan divide.