Why Admitting Women to Combat May Not Ensure Career Equality in America's All-Volunteer Military

Connect with the author

With great fanfare on January 23, 2013, then Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta announced that women serving in the U.S. military would henceforth be permitted to serve in combat. This was seen as opening the doors for full women’s advancement in military careers, because combat experience was widely viewed as a prerequisite for advancement to top ranks in all branches of the U.S. military. The best evidence suggests, however, that the 2013 change may not suffice to equalize opportunities for military women.

The Long-Term Picture for Men and Women in the Military

The removal of the combat bar followed many earlier steps taken over recent decades to include women in a growing range of military roles. Between 1973 and 1975, women were admitted to the previously all-male domain of flight training in the Navy and the Air Force, and in 1978, women were allowed to serve on non-combat ships. In 1992 came repeal of the Defense Authorization Act prohibition that had kept women from flying combat aircraft in the Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps, followed in 2011 by the admission of females to submarine service.

Female-to-Male Ratio by Military Rank

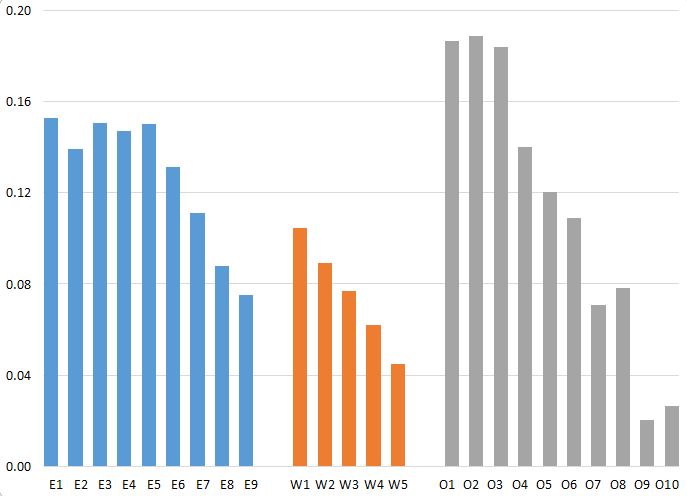

Military women have had a daunting mountain to climb to achieve career equality. The situation as of 2010 is dramatized by striking Department of Defense data on the “gender ratio” – the number of women relative to number of men – at each rank in the U.S. military hierarchy. The data add up the numbers of men and women in each rank across all four military branches, the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. Enlisted people, warrant officers, and commissioned officers are each shown separately – and each has its own separate ladder of ranks. Overall, the figure shows that women are less than one fifth as numerous as men in all U.S. military ranks – and they are far less numerous in most ranks. With only a few exceptions (the step from enlisted rank two to three, and the step from commissioned officer ranks seven to eight and nine to ten), the proportion of women decreases as we move up the ladder of ranks.

Another way to compare men and women in the U.S. military is by putting them on a single scale using base pay at each rank. This allows us to measure the relationship between the gender ratio and pay across the entire military hierarchy. Base pay is a standard indicator of occupational or professional prestige in American society as a whole, and it can also serve as an indicator of true standing in the military hierarchy. When we did this pay analysis, we discovered that as one moves up the pay scale, there is a clear downward trend in the presence of women. Across all four military branches analyzed together, the correlation between the gender ratio and base pay is strongly negative (–0.73) – that is, the better paid ranks have markedly fewer women. Negative correlations vary for the branches considered separately, but the basic story remains the same.

What Holds Military Women Back?

Lagging career advancement for military women could be due to one or both of two basic realities. Women may be less likely than men to be promoted; and they may not choose to stay in the military as long as their male counterparts do. Of course, these may well be connected – if women depart because they lack full opportunities for advancement, for various reasons:

- Supports such as educational programs, family help, or special mentoring may be insufficient to encourage and enable most women to pursue long term careers.

- Engrained biases may discourage many women from seeking promotions; and women may not be strongly recruited into established gateways to officer posts such as the military academies, officer candidate schools, and the Reserve Officer Training Corps in colleges and universities.

- Recently publicized sexual misconduct in the military may discourage women.

Factors such as these have received less attention than military women’s lack of combat experience, which is seen as the key prerequisite for advancement, especially to higher officer ranks. Ironically, if the military continues to make combat experience the most important gateway to top officer positions, then anyone cheering for more gender equity will be in the uncomfortable position of hoping for new conflicts to spur military women’s prospects.

But new conflicts and military deployments to war zones might not even suffice. Other factors holding military women back could remain in play, or even become more pronounced in wartime. What is more, women enrolled in the military might not seek out combat deployments as readily as most men. Under any scenario, therefore, large numbers of women may not make their way into the highest echelons of the U.S. military services anytime soon. Even with legal barriers removed, military officerships may remain predominately a male preserve.