By Gunther Peck, Duke University

Overview:

In the wake of Women’s marches across the United States Donald Trump, the new U.S. President, articulated a thought that had in fact been on the minds of many marchers: “why didn’t these people vote?” If even some of these marchers had not voted, could that explain how Hillary Clinton somehow managed to lose an election that even Donald Trump thought she would win? We will never know how many marchers did or did not vote. But the remarkable enthusiasm gap between this new protest movement and the heavy lifting in the recent Clinton presidential campaign raises a pressing question: how can Democrats more effectively mobilize their moral energy and numerical strength into electoral victories in the future?

For answers, we still need to learn more about how and why Clinton lost. Explanations thus far have focused primarily on messaging failures, FBI director Comey’s investigation, Russian meddling, and the importance of a profound rural/urban split across the nation. But few have considered how and where the Clinton campaign mobilized voters. A closer look at the ground game in the battleground state of North Carolina reveals a simpler explanation for her loss there and a lesson for progressives seeking to win in the future: top-down organizing that ignored local knowledge and an urban focus that wrote off most rural voters until it was too late to organize them effectively. Understanding the history of success and failure in mobilizing voters in North Carolina provides progressives a clear path forward, a model for building an enduring, movement-based Democratic majority in North Carolina and across the nation. I offer three takeaways for how progressives can build enduring Democratic majorities in North Carolina in the future. They are as follows:

Big data does not create an enduring electoral majority. It must be connected to the local knowledge and insights of local actors and organizers.

Geography and Voter Mobility matter as much as metrics. Where statewide campaigns organize and set up local field offices matter. Democrats can’t ignore rural communities and expect to win statewide in NC. Transportation also matters. Turning out transient and sporadic voters are key parts of any winning strategy for Democrats; finding them in the first place and then mobilizing them is essential to reaching other unregistered voters who comprise the latent Democratic majority.

Creating movement culture is essential to building long-term political organization and success. Movement culture is a form of moral capital that emerges when local people and their organizers craft powerful, justice-based messages that mobilize people and communities simultaneously, empowering them in the process of building a political campaign.[i] Movement culture for progressives means not only articulating a justice-based message, but also using an organizing strategy that focuses on where sporadic voters live and work, while empowering them in the process of building movement culture. The time frame of movement culture is historical, not one election cycle.

History Lessons

Not long ago, North Carolina was seen to be safely conservative and Republican at the Presidential level. Between 1964 and 2004, North Carolina voted for the Democratic presidential candidate just once. Since 2008, however, when North Carolina surprised most pundits in voting for Democratic candidate Barack Obama, the state has become one of the most hotly contested swing states in the country. To understand why Democrats lost ground in North Carolina in the Presidential race in 2016, we need to look at broader historical trends over the past five election cycles. That historical angle suggests how Democrats can win at all levels in the future, regardless if there is a transformational figure atop the ticket like Barack Obama or a heavier lift as was the case in getting out the vote for Hillary Clinton.[ii]

Success: Organizing a Progressive Majority in Urban North Carolina

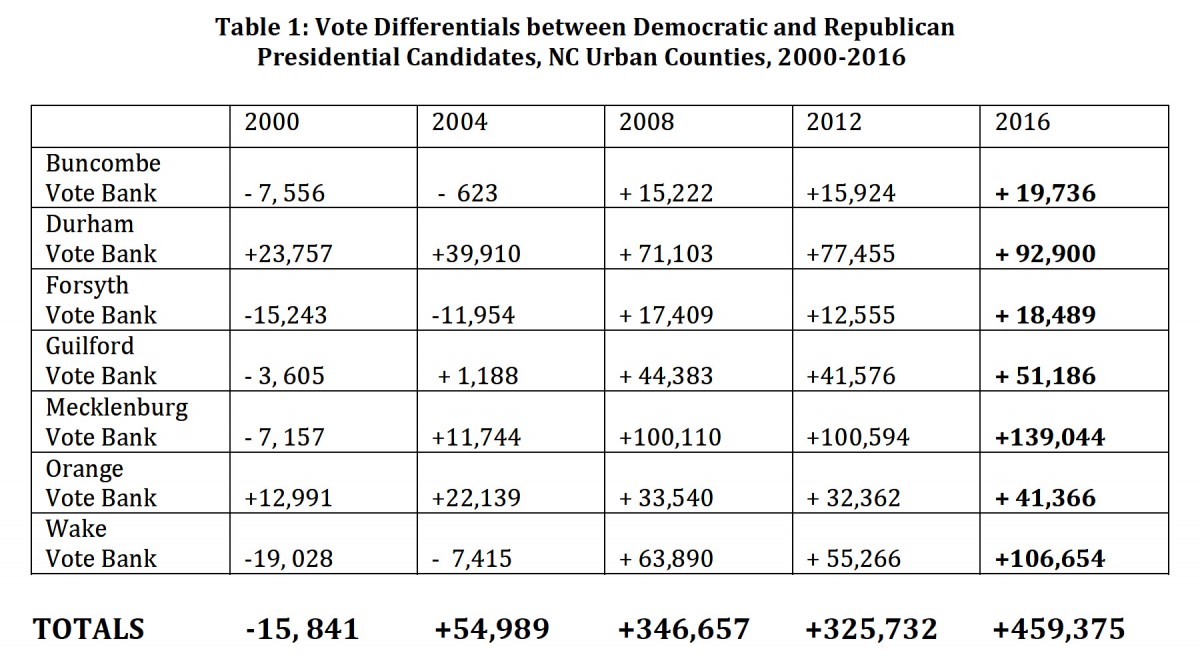

The emergence of North Carolina’s urban counties – Buncombe (Asheville), Durham (Durham), Forsyth (Winston-Salem), Guilford (Greensboro), Mecklenburg (Charlotte), Orange (Chapel Hill), and Wake (Raleigh) – as Democratic strongholds is a relatively recent development. Although pundits have mostly attributed this emergence to demographic changes associated with the in-migration of Northerners working in tech industries and to population growth, the shift to Democratic majorities in fact happened primarily in two election cycles, 2008 and 2016, as Table One indicates.[iii] Indeed, just two of these seven counties fielded majorities for Al Gore in 2000. In 2008, however, these counties expanded their “vote bank” for the Democratic nominee from 55 to 347 thousand votes, a remarkable surge that can not be explained by population increases or by demographic shifts. The Democratic urban majority declined slightly in 2012, but expanded dramatically again in 2016, ballooning to almost half a million more Democratic votes for President than Republican votes in these seven core urban counties. These counties are now some of the bluest in the South, as well as the entire country. It’s a transformation that warrants detailed attention.

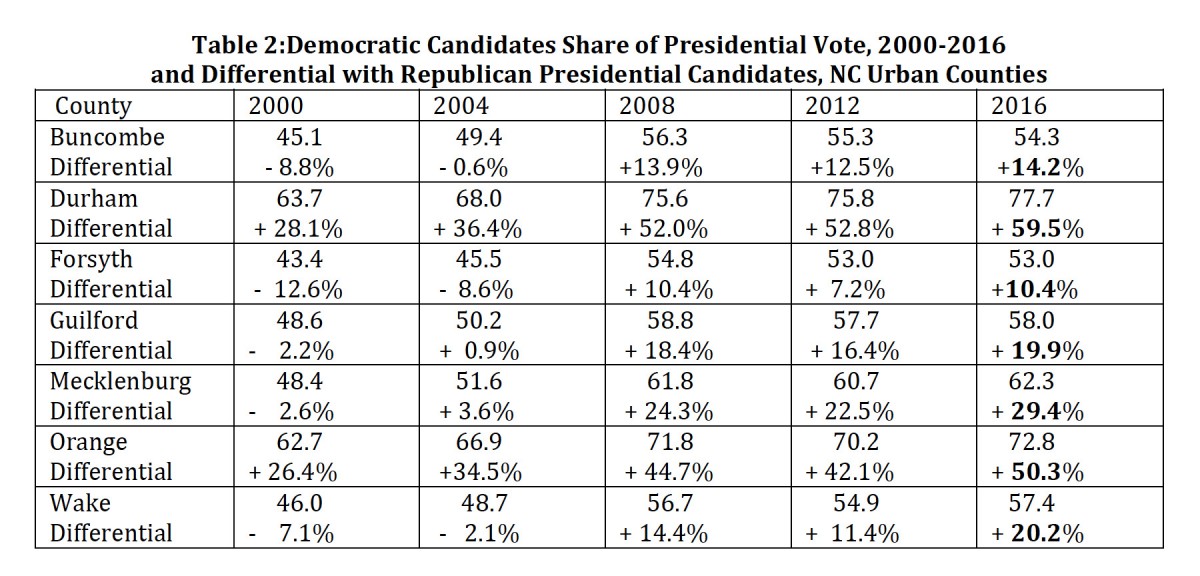

Part of that shift reflected shifting partisan loyalties as table 2 indicates. The growth of the Democrats’ share of the electorate in these core urban counties has been stunning. Durham has remained the most liberal county in the state throughout the period, expanding its majority from 64% to 78% Democratic, with the differential margin over the Republican candidate expanding from 28% to an astounding 59%. Perhaps most consequential, however, have been the shifts in both Wake and Mecklenburg counties, the two most populous in the state. Mecklenburg in fact saw the biggest increase in Democratic voting strength, moving from 46% support in 2000 to 63% in 2016, replacing an eight point Democratic deficit with a thirty point Democratic majority.

Equally important, the size of the electorate dramatically increased in all seven counties, reflecting the success of sustained voter registration efforts. The growth of this Democratic majority did not reflect demographic trends alone as Northerners and others have moved to the Triangle's high tech industries, as so many commentators have suggested. Rather the increase in the size of the Democratic vote bank were episodic rather than steady, with dramatic gains in 2008 and 2016 accounting for most of the growth of Democratic voting strength. This suggests that the partisan shift reflected not so much Republican voters becoming Democrats – the number of Republican voters in these counties has remained relatively constant across the last five election cycles, – but rather a story of disengaged citizens becoming voters, many of them for the first time, casting ballots for Barack Obama in 2008 and for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Local Knowledge and Voter Registration in Durham County

The biggest statewide voter registration drive occurred in 2008, when more than half a million new voters were added to the state’s voting rolls. Both national and local groups were involved in that successful expansion of the franchise. Certainly, much of that increase in voter registration was spearheaded by Obama organizers (OFA). But in most urban counties, a diverse host of local groups participated and shaped the larger success of OFA organizers.[iv]

In Durham, the county with the highest per capita expansion in voter registration of any county in the state in 2008, a volunteer-led group, Durham for Obama (DFO), was formed in February 2008, six weeks before any Obama organizers arrived. When OFA opened its first field office in March 2008, more than three thousand new voters had already been registered county-wide, and DFO possessed seven hundred active volunteers. Over the summer, when OFA organizers left, DFO never stopped organizing but held daily registration drives in Walmart parking lots, barber shops, the downtown bus station, and the Durham farmer’s market, finding new voters in places of heavy pedestrian traffic across the county. When an entirely new group of OFA organizers arrived in August 2008, an additional five thousand voters had been registered, and DFO had grown its ranks to just over four thousand people. Local knowledge was crucial in generating the historic turnout in Durham County and across the state. All told, local organizations along with Obama organizers registered more than 26,000 new voters in Durham County in 2008. Because these new registrants possessed up-to-date information, they were easier to mobilize in the fall election with nearly 90% of them voting.[v]

In the wake of the success of the 2008 campaign, however, few local actors received much attention or credit for the extraordinary “ground game” that turned North Carolina blue for the first time in a half century. Most analyses of President Obama’s historic victory highlighted the role of big data or voter identification technologies that helped Obama organizers effectively target their key cohorts. While such data certainly helped OFA organizers create vitally important walk lists for local volunteers, it did not mobilize voters or volunteers. Local people did that work, along with a diverse cohort of local and extra-local organizations like the NAACP, Moveon, neighborhood churches, and student organizations on all of Durham’s college campuses. Nor did “big data” grow North Carolina’s democracy because so many of these new registrants were formerly invisible in even the best voter lists. Finding these “sporadic” or formerly invisible voters did summon local knowledge and local actors, however. Indeed, without the knowledge, participation, and leadership of local actors and organizations, the dramatic expansion of voter registration rolls in Durham and across North Carolina would not have occurred.

In the run-up to the 2016 election, voter registration in Durham County was again led by volunteer-run local organizations with local knowledge. Beginning in 2015, months before a single Clinton campaign office opened, You Can Vote, a nonpartisan group dedicated to expanding voting rights across the state, sought out the same local hot spots for finding sporadic voters as DFO had previously, registering 12,000 new citizens across Durham, Orange, and Wake Counties. Like DFO, they targeted the downtown bus station, shopping malls, farmer’s markets, and community wide festivals where people congregated. Other groups, including the People’s Alliance, Advance Carolina, and local chapters of North Carolina’s NAACP, helped thousands of new African American and student voters get registered or updated their registrations in Durham and across the state. The work of the Clinton campaign organizers also played a critical role in registering voters once they arrived in the summer. Together, local and national organizers added an additional 21 thousand people to Durham County voter rolls in 2016. The result of that registration effort was clearly manifest in the final vote tallies for the county. Even though turnout in Durham County dipped slightly to 66% from 68% in 2012, the county’s vote bank for Democrats still grew by 16 thousand votes, expanding the Democratic majority from 76 to 78 percent.[vi]

Transportation and Voter Mobilization

Transportation was an essential element of how local and national organizers mobilized voters in Durham in 2008 and 2016. As citizen-led voter registration efforts in Durham County reached a diminishing return in early September, 2008, volunteers travelled out of Durham County, sending DFO volunteers to Granville County (Oxford and Henderson), Person County (Roxboro), and Wayne County (Goldsboro). One group of fifty volunteers from Durham registered over 800 voters in Goldsboro on one Saturday in early October, providing the newly opened Obama field office with a list of nearly one hundred new Goldsboro volunteers, many of them recently registered to vote. That organizing helped make Wayne County, normally a solidly Republican County, genuinely competitive, cutting a 24 margin in 2004 to just 8 points in 2008.

On Election Day in Durham in 2008, transportation again emerged as a central part of DFO’s GOTV effort. With an abundance of more than one thousand Election Day volunteers, organizers for DFO and OFA, working from a home in Trinity Park dubbed “the launch pad,” decided to turn all canvassers into drivers. If canvassers found even one voter who had not yet voted, she/he offered to drive the voter to their polling place, then asked her or him whether they knew of anyone else who had not yet voted. Although “turf” and the big data behind it remained central to the GOTV effort, canvasser/drivers experienced surprising success finding caches of sporadic voters by relying on the best local knowledge available on election day: the same sporadic voters who knew which of their friends and family had and had not yet voted. One DFO volunteer left his turf at 10 am and finally returned to the launch pad at 4:30 pm, having driven eleven voters to polls in five precincts all over the county. That effort was crucial in raising Durham’s turnout to 77% by the end of Election Day, the second highest county turnout in the state and the biggest plurality for the President-elect in the state, a remarkable transformation for a county that had just recently lagged all NC counties in turnout in the 2000 Presidential race.[vii]

In 2016, Durham volunteers not only focused on finding “sporadic” voters in neighborhoods, working with both the Clinton Campaign and Advance Carolina, but also made transportation a focus of their organizing, despite national organizers’ official disregard of those needs. DFO volunteers not only arranged rides for every voter needing them that local Clinton campaign volunteers identified from their canvassing work, but they also canvassed every public transit rider at the downtown bus stations in both Durham and Wake Counties during early voting. Of the 1500 citizens that DFO canvassers drove to early voting sites from downtown bus stations, nearly half were first time registrants or had not voted in years. These sporadic voters proved crucial to finding additional groups of voters not accessible to canvassers with turf. Many transit riders lived in retirement homes or homeless shelters that forbid access to canvassers. Having driven residents to vote and then back to their homes, DFO volunteers gained access to these facilities and arranged rides for hundreds of additional voters in both counties.[viii]

Focusing on people in motion was tolerated or dismissed by national Clinton staff, however, much as it had been in 2012, when OFA organizers kept volunteers confined to working exclusively within their local neighborhoods. That door knocking strategy left key neighborhoods in Durham County under-canvassed in 2012. As a strategy, it not only ignored local knowledge and leadership, but also demoralized volunteers across the county who had been key actors in building the Obama wave of 2008. In 2016, Clinton campaign managers at the national level insisted that canvassers focus solely on the voters they had targeted, telling volunteers to ignore citizens who were registered at the wrong address or who were simply walking around a given neighborhood. Canvassing people in motion, Clinton and Obama campaign managers believed, only slowed down the canvass and could not be counted. But that presumption consistently ignored the desires, knowledge, and capacities of local volunteers and their own local field organizers who often felt demoralized by the campaign’s relentless emphasis on metrics over voters. Volunteers complained they were chasing phantoms rather than canvassing people, trying to find citizens who had moved since last voting, while ignoring the newest citizens who had moved into the same dwellings.[ix]

Put simply, national organizers could have grown an even bigger progressive majority in N.C.’s urban counties had they trusted the insights of local activists and their own local field organizers.[x] The reason national campaign managers missed some of the local opportunities in counties like Durham reflected the ways lessons for each national campaign have been written: by campaign officials at considerable distance from local actors and organizations. These campaign officials did not see local networks, bus-stops, transient people on the go, but instead saw data, which, if crunched more creatively, possessed the secret, they believed, to electoral success. By prioritizing door knock metrics over voters, national campaign managers consistently trusted the so-called wisdom of big data over local people, ignoring more efficient and productive ways of mobilizing local people.[xi]

Creating Movement Culture

If registering new progressive voters was key to the dramatic expansion of a progressive Democratic majority, the way local organizers in Durham engaged fellow citizens – as a justice-based movement – was even more important. Movement culture emerged in Durham not from any dedication to metrics but from a sense of moral engagement that infused efforts to grow the Democracy by empowering citizens to speak and to be heard. In 2008, DFO organizers described canvassing less as a script and more as a process of engagement through listening, where volunteers were encouraged to hear voters’ doubts first, and then offer open-hearted testimony about why voting mattered to them, why democracy itself was a conversation and a project about creating justice -- economic, political, social -- from the bottom up. Every person canvassed by DFO in 2008 was asked if they were interested in volunteering and joining the effort. One in ten new registrants in fact joined DFO in 2008, swelling the organization to over 11,000 members by Election Day. Remarkably, better than one out of ten Durham residents voting for Obama in 2008 either donated money to the campaign or volunteered.[xii]

Movement culture in 2016 was more elusive, as the national campaigns highlighted personality flaws, fears, and anxieties rather than aspirations. But with the help of Advance Carolina, a new organization dedicated to building Black political and economic power, DFO volunteers emphasized the importance of statewide races, which featured six African Americans running for statewide office, including Mike Morgan, a candidate for State Supreme Court. Local volunteers for DFO and Advance Carolina recognized that Mike Morgan’s election would shift the court’s balance to a progressive majority, enabling challenges to racial gerrymandering to be heard, a key demand of the Moral Monday movement that had transformed the narrative about Pat McCrory, North Carolina’s recently defeated Republican Governor.[xiii] “Justice is on the ballot,” DFO volunteers made clear to sporadic or unregistered voters, an argument that proved persuasive to many citizens who were reluctant to vote for Clinton but wanted to vote for Progressive Democrats in statewide races and against NC’s Republican leaders.

The rapid transformation of North Carolina’s urban counties into a powerful Democratic voting block, then, cannot be understood as a triumph of big data that allegedly makes democratic turnout a precise science. Certainly, the energy, insights, and manpower that national organizers brought to urban North Carolina in 2008 and 2016 played an important role in nurturing and turning out Democratic majorities. But absent local organizers, the voter registration expansions would have been much smaller and the GOTV work would have been less effective. More important, local organizers have continued the work of building political power after national organizers leave. When national organizers return every four years, it has been local organizers who have mobilized volunteers with local knowledge about how and where to reach sporadic voters. At its best, the collaboration between local and national organizers provides a model for how to build a powerful movement culture and Democratic majority simultaneously across several election cycles. To understand why that movement culture, based primarily in NC’s urban counties in 2016, was not enough to keep NC blue for Hilary Clinton, we need to examine organizing efforts and electoral returns in some of NC’s key rural counties.

Democratic Failure in the Countryside

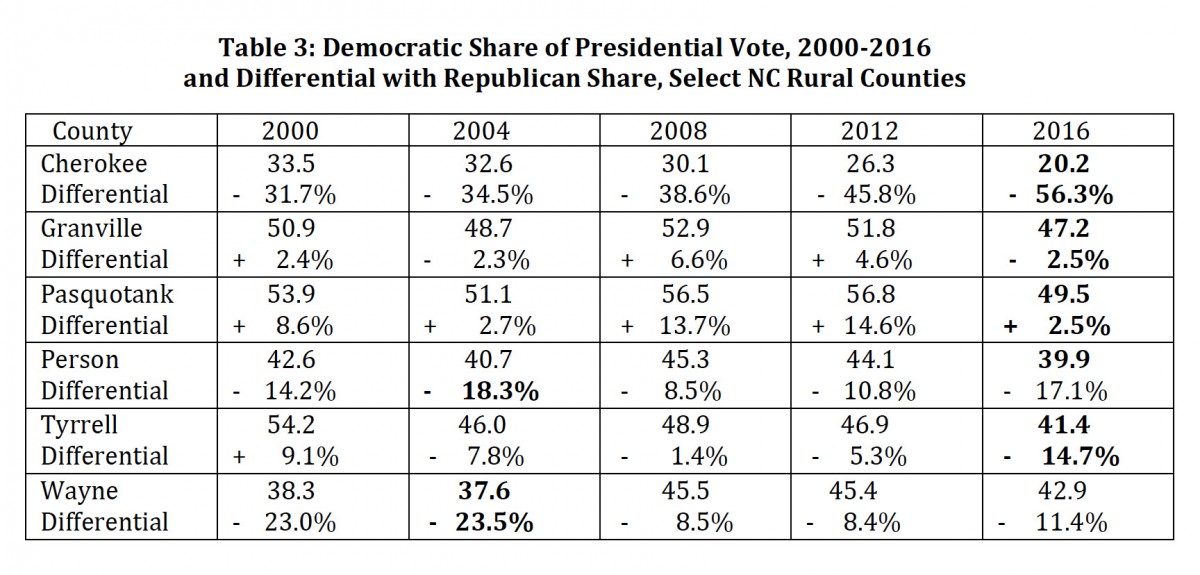

Had Clinton organizers looked at table one before the election, they might have celebrated, as the additional 135,000 Democratic votes in NC’s urban counties was more than enough to offset the losing margin in 2012 of 90,000 votes statewide. But rural counties hemorrhaged more than 200,000 Democratic votes in 2016, eclipsing the impressive mobilizations in Durham, Wake, and Mecklenburg counties. As table 3 illustrates, some of the shift to the Republican Party in rural areas had been happening steadily since 2000 as the diminishing returns in Cherokee County highlight, NC’s western-most county. But an examination of several other rural counties in the Piedmont and the black belt presents a more complex pattern. What is abundantly clear, first, is that there existed a modest but vitally important “Obama wave” across rural North Carolina in 2008 and 2012, one that did not necessarily create outright county Democratic majorities, but cut into the vote margins that Republicans enjoyed before the Obama Presidency.

Person County, just north of Durham and home to Roxboro, is a good illustration. The Obama campaign opened a field office there in 2008 and again in 2012, competing for all kinds of voters and, importantly, providing a space for visible inter-racial organizing in a highly segregated southern manufacturing town. [xiv] The results were modest but generated a significant dent in the Republican majority, which dropped from 18 to 8 percent in 2008. In 2008 and 2012, Goldsboro (Wayne County), Elizabeth City(Pasquotank County), Oxford (Granville County) and Roxboro (Person County) each had Obama field offices that coordinated registration drives and GOTV efforts with local groups. Such efforts trimmed Republican majorities or, in the case of Granville County, built modest Democratic majorities.

In 2016, the vast majority of North Carolina’s rural counties initially had no dedicated Clinton field office. Clinton’s rural organizers, most of them young people with few local ties, were scattered across large geographies with little logistical support, in sharp contrast to organizers in the state’s urban counties. The Clinton website did have a neat graphic, informing the internet user where the nearest office was based on your zip code. For Democrats in Oxford in 2016, that listed office was in downtown Durham, 31 miles away. The Clinton Campaign did belatedly open an office in Oxford, but it was a case of too little too late, especially considering the time necessary to cultivate the ties and trust among rural voters that most effectively mobilize them to the polls.

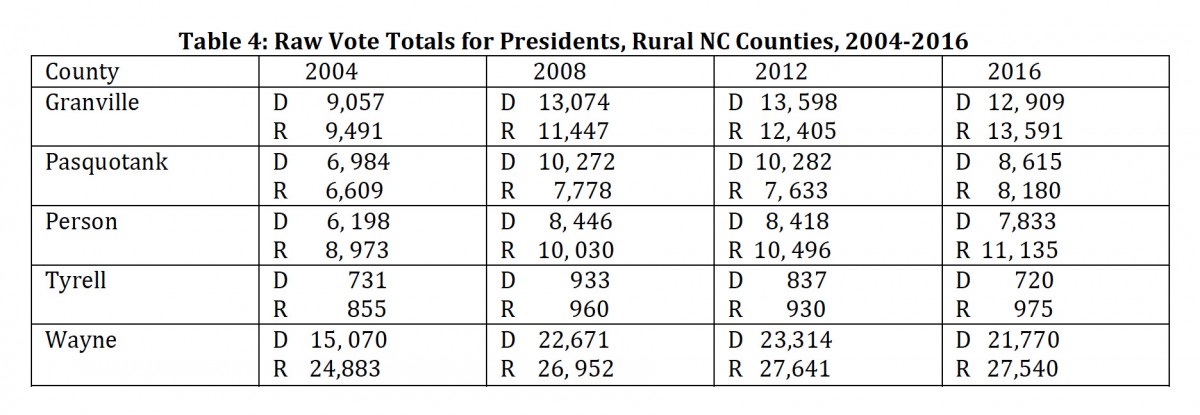

The consequences of the Clinton campaign’s mistake are quite visible in hindsight, but were also apparent in the waning days of the GOTV effort in Durham County, when most of Durham County’s hired Clinton organizers spent much of the final week of early voting working in Oxford and Roxboro. A look at the size of the turnout in rural counties underscores the missed opportunity for Clinton organizers. (See Table 4) The number of Republican voters in Tyrell County was not substantially different between 2008 and 2016. What changed were the number of Democratic voters showing up at the polls, which dropped by roughly 20%. In short, there was little Trump wave in eastern North Carolina, but rather a depressed turnout of sporadic Democrat voters.

In Person and Granville Counties, by contrast, one can detect a modest Trump wave. But even here the electoral returns suggest that the sporadic Democratic voters who had buoyed rural county returns in 2008 and 2012 simply did not show up in 2016. A combination of factors account for that fact. Voter suppression was a very real challenge in Granville County and other rural counties across North Carolina. In contrast to previous elections when the Voting Rights Act was still being enforced, there was just one early vote site open in Granville County in 2016, a fact that vastly complicated the challenge of reaching and transporting isolated Democratic voters in rural counties to the polls. The supply of urban volunteers coming to rural counties like Person and Granville also dropped dramatically in 2016, reflecting the lack of sustained commitment by Clinton's national organizers to rural North Carolina. Add to that the normal challenges of organizing rural voters – who responded best to sustained organizing and a time frame that works with and through local actors – and it becomes clearer why the Clinton campaign's top-down approach and compressed time frame failed to generate much sense of movement culture in Oxford. Voter registration efforts for Democrats dropped accordingly, with many recently registered men and women who comprise the latent Democratic majority staying home in 2016, despite the heroic efforts of individual Clinton organizers.

Future national political organizers need to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors in North Carolina. If the Clinton campaign neglected sporadic Democrats in rural North Carolina counties until it was too late to reach them, Obama organizers also missed important opportunities to build a bigger Democratic majority with rural voters in 2012. Although field offices in towns like Elizabeth City and Goldsboro maintained Democratic strength in 2012, they did not directly reach out to voters living in rural areas, despite credible proposals by local organizers to do so. President Obama’s campaign manager Jim Messina did in fact listen to a proposal by historian Tim Tyson and Ken Lewis, an African American lawyer and activist who ran for US Senate during the disastrous 2010 election cycle, to hire a hundred young rural organizers in the summer of 2012 to register “another Durham” within North Carolina’s rural black belt. But Messina declined to fund or support it, dismissing the proposal of these savvy local actors because it did not fit the top down “door knock” script he and others had devised for President Obama’s re-election.[xv]

Conclusion:

For progressive North Carolinians, there is a roadmap to victory in the lessons we can learn from analyzing the successes and failures of North Carolina’s presidential campaigns over the past five cycles, a history that underscores three takeaways for progressives seeking to build a more enduring and dynamic Democratic majority.

1. Because big data alone is not enough to win, national campaign organizers need to collaborate with local actors and local organizers in building sustained political organization.

National campaigns must recognize that their one-election horizon does not build a long-term political majority, nor does it help Democrats at the state level get elected to statewide office. Without the organizing infrastructure and knowledge that local organizers possess, even the most up-to-date VAN list will not mobilize the aspirations of a community. Local political actors, in turn, need to see justice as an ongoing political project, not one that can wait on national organizers to return every four years. To that end, groups like You Can Vote, Advance Carolina, state chapters of the NAACP, and DFO have each dedicated themselves to building political and moral engagement beyond one election cycle. Whether the next Democratic presidential campaign recognizes their importance remains to be seen.

2. Geography and Voter Mobility Matter.

To be successful statewide, national organizers need to consider not just how and why NC’s urban counties successfully mobilized in 2016, but also where they attempt to find sporadic and unregistered supporters. To win in North Carolina, Democrats will need to devote resources to rural counties and find ways to collaborate with local actors there in building long term organizing strength in every county in the state.

Mobilizing citizens also means attending to the transportation needs of sporadic voters. They are “local knowledge” experts, whose relevance and power is grossly under-estimated by big data and metrics, for precisely the reason that so many of them are not where they are supposed to be. Organizers and canvassers should choose voters over metrics, transient people on their way to work over door knock metrics, whenever possible. When volunteers are told to refuse to canvass voters who show up at the wrong address, ignoring the new residents who have moved in but need to be registered, vital opportunities to grow the latent Democratic majority are missed. The bird in hand is not only better than two in the bush, but can lead you to two friends after the bird has voted. Every sporadic voter – every person not in the best VAN list – should be understood as a canvasser’s best ally in finding more of the nonvoters in our communities.

3. Creating movement culture provides a blueprint for how to build long-term political organization and success.

Building movement culture means not only finding sporadic voters, but also listening to their needs and empowering them to become consistent voters and even fellow organizers. Building a movement culture takes place when we craft morally powerful justice-based messages that empower people in the process of building a campaign. Volunteers, voters, and unregistered people alike need to see themselves fully incorporated within not just the outcome of an election, but in the process of how we move forward together as citizens.

Movement cultures are built first and foremost on canvassing rather than advertising; on engaged listening between citizens, who seek to witness and activate the moral center of every citizen an organizer or canvasser encounters. The Moral Monday movement built a political message that successfully resisted Governor McCrory at the ballot box in 2016, not with ads but with moral convictions that were above partisan rhetoric and with a powerful sense of history and history-making. As many local activists understood in NC’s urban counties, justice was indeed on the ballot in 2016. Candidate Clinton benefited from that energy, but her national campaign managers did not directly tap into that message outside of the urban centers where a multitude of people were organizing on her behalf.

If progressives are to win again, they need to learn from the mistakes and successes of recent national campaigns. Rural America is not one unified region with one cultural narrative and one political preference. In North Carolina, there are Democrats aplenty in rural regions, as Obama’s rural wave underscores. The good news for progressives is that there is a clear path forward. Fighting for the voting rights of sporadic voters, whether Democrats, Independents, or Republicans, and mobilizing them in both rural and urban counties will be key to the success of progressives in North Carolina and elsewhere. Big data does not provide answers to why Democrats lost, nor will it help reach the estimated 800,000 North Carolina citizens who are currently unregistered, most of them Democratic leaning. Only collaborations between local and national organizers in both urban and rural counties will build an enduring Democratic majority. Progressives know how to win; they just have to bring their organizing skills, their commitment to justice as a political project, and their respect for local knowledge to the rural voters who like them crave the justice that has long generated movement culture in America.

Endnotes

[i] I have adapted the term “movement culture” from the work of the prizewinning historian of American populism, Lawrence Goodwyn, who emphasized first its independence from traditional political campaign work. For an elaboration of the concept and movement culture’s power in reshaping American political history, see Goodwyn The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (New York: Oxford, 1978), xviii. For a fuller explanation of how “movement culture” thrived on Durham County, NC before, during, and after the Obama wave of 2008, see my forthcoming article “Movement Culture in Durham, NC,” in Paul Ortiz and Wesley Hogan, eds., The Enduring Power of Lawrence Goodwyn’s Work (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming). I have adapted the phrase “moral capital” from the work of historian Christopher Brown, who used it to describe the strategy and moral worldview of the abolitionists, who like the Populists also built a remarkably successful social and political movement . See Christopher Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

[ii] For an excellent overview of North Carolina’s political history and the roots of contemporary polarization in the state, see Karl Campbell, “Tar Heel Politics: An Overview of North Carolina Political History in the Twentieth Century, 1900-1972,” (2010) See also Milton Ready, The Tar Heel State: A History of North Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2005); Pamela Grundy, A Journey Through North Carolina (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publisher, 2008); William A. Link, North Carolina: Change and Tradition in a Southern State (Wheeling, Illinois: Harlan-Davidson Press, 2009).

[iii] All electoral returns have been culled from the raw county returns available at the website of the NC Board of Elections: https://www.ncsbe.gov/Election-Results. By looking at five presidential election cycles in a row, I have been able to highlight both more general trends and important continuities within particular counties. Such an approach de-emphasizes the importance of individual candidates and the criteria that dominate many electoral histories: the absence or presence of a candidate’s charisma, their particular platform, etc. County data makes plainly clear trend lines over time as well as expansions and contractions in the number of citizens participating.

[iv] All turnout figures have been gleaned from the NC Board of Elections.

[v] For a more detailed history of the ground game in Durham County, see Peck, “Movement Culture in Durham, NC.” See also Lawrence Goodwyn, “The Ground Game: Realizing Obama’s Vision in North Carolina,” The Texas Observer, December 12, 2008.

[vi] According to Washington Post reporter Chris Cillizza, depressed turnout in key Democratic counties explains why Clinton lost. That analysis ignores the bigger story in North Carolina of Democratic success by growing the latent Democratic majority with voter registration, as well as the urban/rural split, to which we turn shortly. If turnout numbers in 2016 in NC’s urban counties had matched 2008 levels, Clinton would still have lost the state, though it would have been closer. Reduced turnout also cut two ways. One reason that turnout in Durham was down slightly in 2016 but Democrats grew their vote bank dramatically, was that lots of Republicans in the county stayed home, with five thousand fewer of them showing up to vote. See Chris Cillizza, “What one Wisconsin County can tell us about why Hillary Clinton Lost,” The Washington Post November 21, 2016.

[vii] Volunteers in Durham County’s GOTV effort in 2008 came from local and international destinations. Numerous Canadian and European volunteers signed up to do voter registration and door to door canvassing in the summer and fall of 2008. One of the most active volunteers, “Simon the Dane,” was featured in a short documentary about DFO, available at the following Youtube address: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtL5QymuaDM. The documentary gives a good picture of the “launch pad,” as well as the strategy of making canvassers into drivers.

[viii] Knowledge of the bus stop canvass in Durham and Wake Counties, how it worked and how many voters received rides to vote have been compiled by the author who, along with Faulkner Fox, co-founder of DFO, organized the GOTV efforts from the “launch pad” in 2008 and at county bus stations in 2012, 2014, and 2016.

[ix] First hand testimony of dozens of DFO volunteers in 2012 who sought, with mixed success, to persuade OFA organizers to allow volunteers to canvass outside their own immediate precincts or “turf.” In 2016, Durham County volunteers were fortunate to work with a far more collaborative and creative group of Clinton organizers, who actively supported the bus-stop canvass and also collaborated with local organizers to drive all voters needing rides that Clinton canvassers encountered during GOTV. But efforts by DFO organizers to persuade national Clinton campaign staff, including Robbie Mook, to create a statewide driver/canvasser plan, targeted for African American voters needing assistance in both rural and urban areas, were rebuffed.

[x] For a similar critique of the inflexibility of Clinton’s national campaign staff, see Edward-Isaac Dovere, “How Clinton lost Michigan – and blew the election: Across Battlegrounds, Democrats blame HQ’s stubborn commitment to a one-size-fits-all strategy,” Politico, December 14, 2016. Dovere’s piece is one of the few that focuses on how Clinton’s ground game worked – or rather did not – in battleground states.

[xi]For an analysis of how and why Organizing for America, a grass-roots oriented political movement became a top-down re-election organization in the hands of Jim Messina, see Ari Berman, “Herding Donkeys,” The Nation, September 29, 2010; Berman, “Jim Messina, Obama’s Enforcer,” The Nation, March 30, 2011.

[xii] On the centrality of justice and history to DFO’s voter registration efforts in the fall of 2008, see Lawrence Goodwyn, “The Ground Game.” The estimation that better than one in ten of Durham’s Obama voters gave money or volunteered is based on a simple ratio of the number of Obama votes in Durham – 103,000 – divided by the number of DFO members in its database the day after the election, at 11,105. Roughly one thousand of those members were extra-local – hailing from ten states and seven countries -- leaving 10,000 Durham-based members in the DFO membership database.

[xiii] On the impact of the Moral Monday movement on the 2016 gubernatorial race, see the blog by Tom Jensen, “Why Pat McCrory Lost and What is Means in Trump’s America,” Public Policy Polling. For discussion of how the Moral Monday movement might serve as a model for opposing Republican Party over-reach under a Trump administration, see Reverend Dr. William Barber II, “North Carolina: A Case Study for Resistance n the Trump Era,” The Nation, December 7, 2016; Dianna Anderson, “The Success of Moral Mondays in North Carolina is a Template for National Resistance,” Shareblue, December 6, 2016.

[xiv] Organizers in Person County in 2008 confronted a very different geography than in Durham, but nonetheless utilized similar methods to find sporadic or unregistered voters. Volunteers registered large numbers of Democratic voters in Wal-Mart parking lots and in local barber shops. Local volunteers also gained access to local African American churches and substantially expanded the number of registered Democrats county-wide.

[xv]Timothy Tyson, “Marching Up to Zio: A Vision of Victory in North Carolina for President Obama and the Democratic Party in 2012,” personal copy. Knowledge of Messina’s failure to adopt the plan comes from a conversation between Tyson and the author, December 16, 2016.