Mass Imprisonment and Growing Distrust in the Law

In 1970, the United States sent about 100 out of every 100,000 of its residents to prison. Since then, the rate of American imprisonment has skyrocketed. By 2010, roughly 500 of every 100,000 American residents were in prison. The United States now incarcerates more of its people than any other nation, and African Americans are imprisoned at six times the rate of whites.

Imprisonment can weaken families and undermine former prisoners’ ability to find stable housing, achieve economic security, and live healthy lives. Unprecedented rates of imprisonment might also erode Americans’ trust in government. Growing distrust in the law could inspire social movements to reduce the number of people in prison. But it could also lead to a self-reproducing cycle whereby growing distrust leads to more punishment and more punishment leads to more distrust.

The Impact of Increasing Imprisonment on Trust in the Law

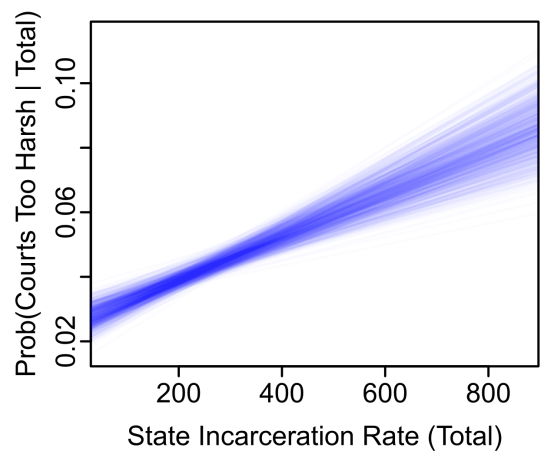

Now more than before the prison boom, Americans are likely to say that the courts are too harsh. The figure above shows that as states’ incarceration rates increased, so too did the probability that residents said the courts are too harsh. Rather than boosting Americans’ confidence in the criminal justice system, the prison boom may thus have shaken it. Racial gaps in trust are also evident:

- African Americans are much more likely than whites to believe that the courts are too harsh. Between 1982 and 2002, the proportion of U.S. whites who said that the courts are too harsh seldom exceeded ten percent in any given state. In contrast, the share of African Americans who view the courts as too harsh ranged from roughly seven percent to thirty percent.

- African Americans’ relatively low estimation of the courts is long standing. Although whites’ skepticism about courts grew in tandem with the white incarceration rate, African Americans’ level of trust did not change with the growing African-American incarceration rate. African Americans have long viewed the courts as excessively severe. Their durable distrust of the law may stem in part from their historical experiences with criminal justice institutions, from Southern convict leasing in the late nineteenth century through racially biased Northern policing in the mid-twentieth century.

Personal Ties to Prisoners May Promote Distrust in the Law

The United States’ high and racially disparate rate of incarceration may affect not only former prisoners’ trust in the law, but the trust of their friends, family, and neighbors as well.

- African Americans who have been to prison or who have a close friend or family member who has been to prison are more likely than those with no ties to prisoners to attribute racial disparity in incarceration to police bias and bias in the courts.

Were African Americans simply interested in deflecting blame from their loved ones, they could just as easily attribute racial disparity in imprisonment to poverty, a lack of jobs, or poor schools. Instead, they restrict their criticism primarily to the police and the courts. Thus, the pervasiveness of incarceration in the lives of many African Americans may lead them to perceive courts and other criminal justice institutions as biased and unfair.

Declining Trust in the Law and the Future of Punishment

Declining trust in criminal justice institutions could have different effects on punishment depending on the public’s response. On the one hand, it may encourage more Americans to support shorter prison terms and a lesser reliance on imprisonment. As the white incarceration rate has increased, more white Americans have viewed the courts as excessively harsh. Growing white dissatisfaction with criminal justice institutions may enable white Americans to imagine a shared fate with their African-American counterparts, who historically have borne the brunt of harsh punishment. But there is still class-based inequality in imprisonment, and institutional barriers block the political influence of those most affected by crime and punishment. These pose formidable challenges to efforts to modify criminal laws and reduce the number of people sent to prison.

On the other hand, declining trust could increase crime and, in turn, punishment. Distrust affects both civilians and the police who patrol their communities. Researchers have found that individuals who believe that the law is legitimate and affords them protection are less likely to break it. Short-run increases in crime due to dwindling distrust may thus enlarge, rather than reduce, the prison population. Moreover, interviews and observations show that African Americans’ suspicion and avoidance of police can lead police to overestimate the level of crime in African-American communities. Justifying widespread arrests is easier when an entire community is rendered suspect. If distrust in the law engenders more punishment, and more punishment more distrust, it may be hard to break free of the self-confirming cycle of racial disparity in imprisonment.