Why California Needs Specific Educational Data on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders

It is no secret that unequal access to education produces racial disparities in the United States – and the state of California is no exception. Many studies document how California’s public higher education system struggles to reduce disparities in college access and success for black and Latino students. Yet conversations about race and educational equity sometimes overlook the Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders who account for one in every seven people in the state. A persistent myth overstates the performance of Asian American students. Despite being people of color, they are often pigeonholed as “model minorities” who have figured out ways to overcome systemic barriers, pick themselves up by their bootstraps, and achieve educational success above and beyond other ethnic groups. However, this misleading model minority mythology has been fueled by mishandled and misleading educational data. We cannot produce meaningful change unless we get the data right.

Misinformation Perpetuated by Overly General Data

When viewed as one homogenous ethnic group, “Asian Americans” appear to be outperforming other minority groups, for example their above average graduation rates in the California State University system. However, combining all Asian ethnicities together into one category provides a misleading picture of what is really happening. Asian Americans are not a homogenous group, they include various ethnic groups – ranging from Chinese Americans to Vietnamese Americans to Pacific Islanders and many others – who live in different places, hold different jobs, and have various levels of educational attainment, income, and immigration histories into the U.S.

Fortunately, a recent report from the Campaign for College Opportunity in partnership with Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles, provides a more realistic glimpse into developments for various subgroups of Asian Americans in California. The conclusions reached by policymakers and advocates are likely to change when they use disaggregated data broken down by these various Asian American groups.

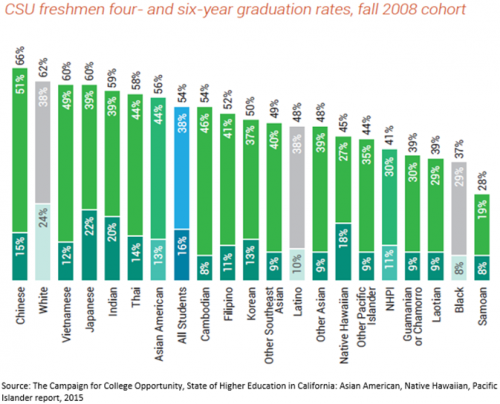

The chart below displays graduation rates for sixteen different subgroups of Asian Americans – and the chart also shows the overall graduation rate for all groups combined, in order to dramatize the difference it makes when we break things down. Although all “Asian Americans” lumped together have a combined graduation rate of 56% -- two percentage points higher than the graduation rate for “all students” in the California State University system – it is easy to see from the subgroup breakdowns that specific sets of students, like Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, are graduating at much lower rates – 45% and 44%, respectively.

At the most troubling extreme, only 8 % of Samoan students graduate from California State Universities in four years, and only 19% in six years, far lower than the graduation rates for their Chinese, Vietnamese, and Japanese counterparts. Furthermore, a close look at the enrollment numbers makes it clear that Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino students – who make up over 60% of the total Asian American population in the California State University system – are driving the stronger aggregated graduation rates so often touted in public. Detailed breakdowns reveal that only five of the 16 subgroups of California Asian Americans are actually performing above average. Gaps still exist between white students and the majority of other ethnic Asians.

Accurate Data Leads to Better Policy

The bottom line is that most educational data used in California do not account for large variations among ethnic groups in the broad Asian American category – and that applies to many measures of student success, not just graduation rates. Policy decisions made with overly general data make it impossible for educators to identify and remedy problems faced by particular underrepresented groups and are thus likely to leave real achievement gaps unaddressed. Many struggling Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian students, for example, could benefit from targeted support services which they may not get if they are lumped in with other groups.

These issues go well beyond California. National, state, and institutional efforts to further educational equity all need high-quality, properly disaggregated data. Recently, advocacy organizations and state legislators in California passed a bill to require California colleges and universities to use and make public specific data for Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander groups. Unfortunately, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed the bill, citing concerns about further stratifying ethnic subcategories. Ultimately, his veto only underscores the importance of persuading policymakers and higher education leaders to collect and rely on realistic data that responds to the complex demographics of students in America’s education systems.

Read more in “The State of Higher Education in California: Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Report,” The Campaign for College Opportunity, September 2015.