Connect with the author

Melissa Johnson, a 38-year-old mother of three, worked for fifteen years as an administrative assistant at the same metro-Detroit law firm, where her co-workers seemed like family. But when the Great Recession hit in 2007, Melissa was laid off. Devastated, she signed up for unemployment benefits and, when no work appeared, she undertook retraining to become a nurse. Unemployment insurance paid Melissa a portion of her former salary for the duration of her training. Without those benefits, her home would have gone into foreclosure. When we spoke with Melissa in summer 2013, she had new work as a nurse – and still had her home.

Melissa’s story shows what U.S. unemployment insurance is supposed to do. But in February 2014, after two months of debate, a minority filibuster in the U.S. Senate blocked continued unemployment benefits for people like Melissa who have been caught in the sustained joblessness that followed the Great Recession. Melissa’s name has been changed to protect her privacy, but her story is real – and far from unique. According to estimates from the U.S. Census, unemployment benefits kept 1.7 million people out of poverty in 2012, including both jobless workers and members of their families.

Much public controversy has surrounded the recent refusal of Congressional Republicans to sustain emergency unemployment benefits. The attention is warranted, because benefits have not previously been cut off during such a prolonged jobs crisis as the one the United States currently finds itself in. Yet this debate should not preclude attention to fundamental, long-standing problems with the financing of unemployment insurance in the United States. For some time, the system has been inadequate. The country can and must do better.

The New Deal Unemployment Insurance System

The truth is that unemployment insurance, especially in ordinary times, could largely pay for itself – and that was what President Roosevelt intended when the program launched in 1935. Employer payroll tax contributions set by law in each state were supposed to cover benefit costs, and the federal government also levied its own unemployment insurance tax on employers to pay for program administration.

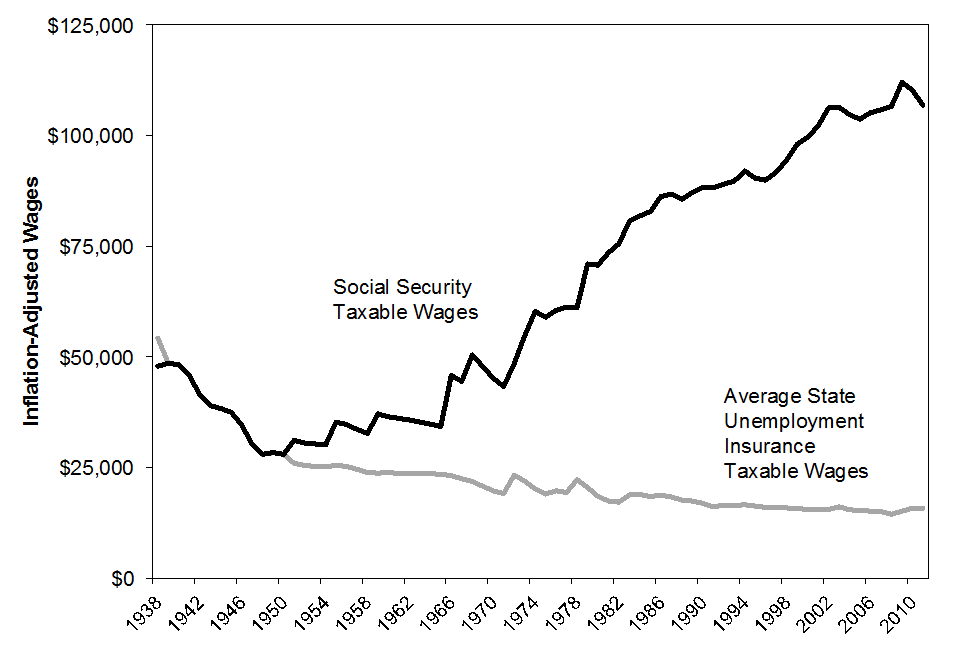

Unlike other New Deal programs, such as Social Security, financing for unemployment insurance has remained largely unchanged – and the failure to update unemployment insurance contributions to keep pace with wage growth is a root cause of today’s problems. While Social Security contributions have increased along with average wages, unemployment insurance contributions from businesses remain relatively unchanged. In fact, adjusted for inflation, the total amount of wages subject to unemployment insurance taxes has actually fallen, as the following figure clearly dramatizes.

In most states today, employers make the same unemployment insurance contribution regardless of whether a worker earns $20,000 or $150,000 per year. Yet when workers lose jobs, those who earned $150,000 while employed receive more in benefits. Meanwhile, federal government contributions to unemployment insurance have also eroded. Just as state contributions have been frozen in time, the federal taxable wage base has been frozen at $7,000 since 1983.

Time to Reform Benefit Finances

The implication is clear: both states and the federal government need to update their unemployment insurance contributions to match growth in wages, just as the federal government does with Social Security. This would strengthen state unemployment insurance finances and reduce the need for the federal government to bail them out during recessions.

Is such a change politically possible? We think so. Americans have historically been very supportive of worker and employer contributions to social insurance programs. Because the tax is currently so low, the increases necessary to fix the system are modest. Today, for each worker earning $7,000 or more, the federal government collects only $42 per year. This is too little to pay for the vitally important help unemployment insurance offers to sustain laid-off workers like Melissa as they get back on their feet in the job market. All American workers need such security in today’s volatile economy – and Congress should lead the way in having the debate we really need about how to reform unemployment benefits for the long haul.