How Public Servants Experience Violence and Abuse While in Office

Many politicians experience psychological abuse and physical violence from their constituents. In addition to the more publicized shootings and threats made against members of Congress, the lives of the mayor and city council of Tacoma Washington were threatened over a proposal to close a bowling alley. Similar threats were made against Stillwater Oklahoma’s city council and mayor over a gun control proposal. In 2016, a West Virginia state senate candidate was hospitalized after being attacked at a fundraiser. Although such attacks may make it difficult for leaders to do their jobs and may stifle the willingness of people to be public servants, little scholarly research has examined violence against politicians in the United States.

To help fill this void, I, along with Sue Thomas, Lori Franklin and others, conducted a survey of U.S. mayors in cities over 30,000. The goal was to estimate the frequency, factors related to, and effects of psychological abuse and physical violence. The survey had a 20% response rate from mayors across 40 states.

Key Findings

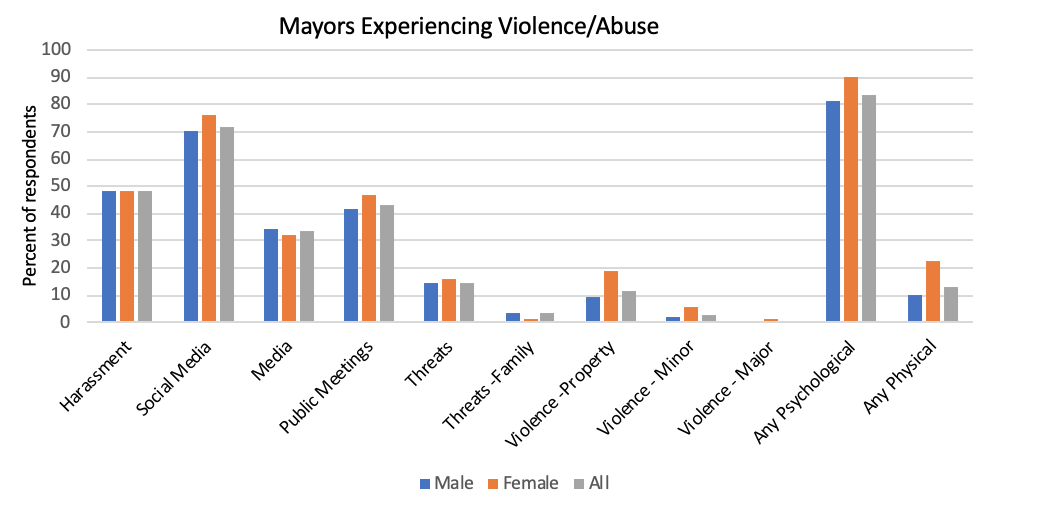

The chart below indicates the percent of mayors (male, female, and total) who reported experiences of abuse and violence either as mayor or as a candidate. In addition to specific types of abuse/violence, we also indicate the percentage who experienced physical violence (property violence, minor or major) and psychological abuse.

The chart indicates that psychological abuse is quite common with around 80 percent experiencing some form of it, and that social media is the most common conduit of psychological abuse, with 70 percent experiencing social media abuse. Physical violence is less common, but still over 10 percent experienced some form of physical violence.

Another key finding is that female mayors experience more psychological abuse and physical violence than men mayors. In fact, sex is the most consistent factors related to whether or not mayors experience violence. Our analysis also indicated that some female mayors are more likely to face violence: strong female mayors, directly-elected female mayors, and female mayors in traditionalistic political cultures. Together, these results offer some support for the theory that female mayors, as disrupters of the status quo, face more violence and abuse than their male counterparts.

Sex was not the only factor that affected the odds that mayors experience violence or abuse. Mayors from large cities, strong mayors (those with veto and appointment powers) and young mayors experienced more abuse and violence, particularly psychological abuse. Mayors of cities with lower crime and education rates were also more likely to experience physical violence. Surprisingly, many political factors such as partisanship of the city, mayors’ party identification and ideology had insignificant relationships with violence with one exception: mayors whose constituents were more conservative than they were experienced less psychological abuse.

Our research also found that the violence and abuse had negative consequences for the mayors. About 18 percent of mayors who reported violence/abuse had intrusive thoughts of the event, nightmares, or avoided reminders of the event, and 39.4 percent experienced irritability, sleep difficulty or difficulty concentrating following violent incidences. In fact, 27.8 percent reported having experienced both types of psychological stress compared to 14.8 percent who experienced just one type. Hence, more than 42 percent of mayors exposed to violence/abuse experienced at least one sign of psychological harm.

The effects on mayors’ ambition was more muted. About 5 percent of mayors who experienced violence/abuse reported that they definitely thought about leaving office, and 11.2 percent said they most likely thought about leaving. Since mayors have already invested much time in their careers, it is not too surprising that most did not consider leaving after experiencing violence or abuse. But several mayors did express concerns that the violence was depressing others’ ambition.

The results suggest that harassment caused the greatest amount of psychological harm and that physical violence, harassment and, to a lesser extent, being disrespected had the greatest negative effects on ambition.

Although our results are interesting, they cannot speak to whether mayors are unique in the levels of violent and abusive experiences. Nor can we speak to whether violence is becoming more common. However, the levels of violence/abuse, particularly psychological abuse is higher than those found in most other careers, and several mayors expressed concerns that violence/abuse, particularly psychological abuse from social media has changed the nature of the job.

Read more at Rebekah Herrick, Sue Thomas, Lori Franklin, Marcia L. Godwin, Eveline Gnabasik & Jean Reith Schroedel, “Physical Violence and Psychological Abuse Against Female and Male Mayors in the United States,” Politics, Groups, and Identities, (2019); Rebekah Herrick, Sue Thomas, Lori Franklin, Marcia L. Godwin, Eveline Gnabasik & Jean Reith Schroedel “Not for the Faint of Heart: Assessing Physical Violence and Psychological Abuse Against U.S. Mayors,” State and Local Government Review 51, no 1 (2019): 57-67; Rebekah Herrick & Lori Franklin, “Is It Safe to Keep This Job? The Costs of Violence on the Psychological Health and Careers of U.S. Mayors,” Social Science Quarterly (Forthcoming).