The Importance of Shifting Public Opinion about Criminal Justice and America's Prison Boom

In the 1950s, the U.S. incarceration rate was roughly on par with the incarceration rates of Finland and Denmark. Today, the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. While the immense economic, social, and political costs of mass incarceration are now well known, the causes of mass incarceration continue to be debated. One cause that is particularly misunderstood is the role of public opinion.

Conventional wisdom suggests that conservative political leaders like Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan led the way toward mass incarceration, and more recent scholarship highlights the contributions of Democratic presidents like Lyndon Johnson and Bill Clinton. But even though past presidents did help to spur rising rates of incarceration, a focus on political leaders misses an important part of the story. The key question is why these (and so many other) political leaders moved in a punitive direction. Public opinion offers much of the answer. The U.S. criminal justice system became the most punitive among all advanced democracies because politicians responded to an increasingly punitive public.

Political Leaders and Rising Incarceration Rates Followed Public Opinion

Internal memos from Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign offer one window into the influence of punitive public attitudes. Even before the Republican nominating convention, the Nixon campaign was analyzing public opinion polls and developing a strategy based on growing public concern about crime. As explained in a memo sent to key members of the campaign in July 1968: “The Gut vote, then, is leaning toward Humphrey. But this group is not happy. It is concerned, in particular, about the following things: 1. Crime. They are worried about the safety of their families. They are sick of permissiveness in the courts, the city halls, and the Administration.” Although the Nixon campaign worried that Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey had an edge in the polls, it believed votes could be gained by appealing to the public’s growing demand for tougher criminal justice. As my review of internal memos reveals, Nixon’s staff focused on polling showing the public’s concern with crime throughout the campaign.

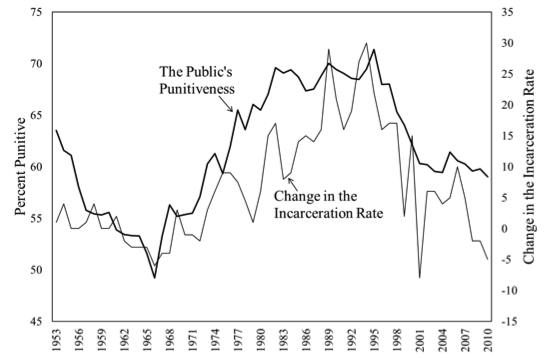

If presidents and other political leaders responded to public opinion, the public could have had a profound influence on rising rates of imprisonment. To get a more complete sense, I developed a measure of the public’s punitiveness that combines information from attitudes about criminal justice policy and punishment as revealed in surveys taken from 1953 to 2010. Relevant questions asked about support for the death penalty, prisons, spending on law enforcement, and the idea that prisons should stress punishment rather than rehabilitation. Questions also probed whether respondents thought the courts were too lenient. By combining responses from 33 such questions repeatedly asked in public opinion surveys (nearly 400 times in total), I created a global measure of public views that spans almost 60 years. As the following figure shows, this measure has closely tracked changes in the incarceration rate – and the strength of the relationship is stunning.

Public Punitiveness and Changes in U.S. Incarceration, 1953 to 2010

Note that even though absolute incarceration rates continued to rise during the late 1990s and 2000s, the key is what drives changes in the incarceration rate. Focusing on changes, this figure shows that not only did the prison rate grow faster as the public became more punitive, but the reverse is also true: as the public became less punitive in the late 1990s and 2000s, incarceration rates rose more slowly and eventually declined. This pattern shows that public opinion plays an important role in the evolution of mass incarceration in the United States.

Declining Public Punitiveness May Allow Reduced Incarceration

Shifting public attitudes were a key factor in the rise of mass incarceration – as also shown by my analyses of political leaders ranging from Barry Goldwater to Lyndon Johnson, along with my examination of state-level incarceration rates and spending on corrections. My results also suggest three key insights for those who now want to reduce mass incarceration.

- Politicians do listen. We are often told that politicians do not listen to ordinary Americans. But when it comes to criminal justice policy, the public has had substantial influence over the last six decades. If the public was a critical factor in the rise of mass incarceration, shifting public attitudes also have the power to encourage reduced incarceration.

- Possibilities for reforms are improving. Since the late 1990s, public attitudes have shifted in a less punitive direction, and even though the U.S. criminal justice system remains extremely punitive – and the Trump Department of Justice is reinforcing many punitive stances – we see evidence of responses to shifting public views, especially at the state and local level. These include the decriminalization of certain drug crimes, some prison closings, bail reform, and bipartisan calls for continued criminal justice reform.

- For reformers, influencing the public is just as important as influencing politicians. With good reason, activists and reformers often demand changes from politicians. But officials and aspiring political leaders respond to the public. When activists identify promising steps to reform criminal justice, informing the public is just as important as contacting politicians.