Why U.S. States Must Increase Efforts to Help Low-Income College Students – and How They Can Do It

Connect with the author

For many students, the thrill of preparing for college is accompanied by a worry about whether they can afford it. Low-income students face new cost barriers due to rapidly rising tuition and fees even as the value of federal Pell Grants has stagnated since 1980. Pell Grants currently cover less than half the price of tuition and fees at many public universities, and even less at most private colleges.

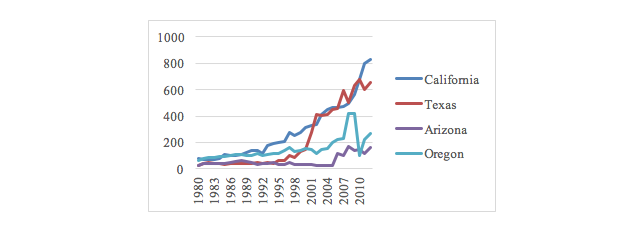

In response to the growing gap between college costs and available federal aid, states have stepped into the gap, but their efforts vary significantly. California, for example, currently spends over $800 per full-time equivalent student, while Arizona spends under $200. Because states will likely remain a vital source of student aid, such variations mean that access to college for low-income students may depend more on where they live than on their academic abilities.

Need-Based Financial Aid Expenditures by Full-Time Equivalent Student, 1980-2012

How California and Texas Became Leaders

How California and Texas Became Leaders

In 1999 and 2000, Texas and California lawmakers significantly expanded their budgetary commitment to need-based financial aid. Working with university governing boards, state boards of postsecondary education, and citizen groups, lawmakers enacted policies that committed each state to provide grants for all eligible, financially needy students attending an accredited institution. This process unfolded in three steps:

- First, higher education research organizations and governing boards published demographic data that indicated impending growth in Hispanic populations as well as low college-completion rates for this group.

- Second, members of higher education governing boards and the legislature argued for expanded aid by pointing out that improving college completion among low-income and minority youth would help the economy and promote equal opportunity. Not doing more to aid such students, they argued, could mean that their state would not be able to meet the demands of a modern, technology-driven economy. The state’s tax base would also suffer, they pointed out, if disadvantaged youth matured into economically marginalized citizens.

- Finally, lawmakers enacted programs that were difficult to reverse because they included provisions designating postsecondary financial aid as an entitlement for all needy students.

A Formula for Policy Breakthroughs

Using arguments linking equity to economic opportunity, California and Texas stakeholders made a strong case for expanding aid through programs that remain popular among lawmakers and voters. The fact that such efforts were successful in two very different political contexts suggests that expanding need-based state aid can be widely popular in states with varied political leanings.

Advocates and policymakers elsewhere can learn several key lessons from the Texas and California experiences:

- Identifying a growing demographic group with lower than average college completion rates can start the ball rolling – by highlighting the need for more educated workers and showing that potential students need more aid.

- Stakeholders can use public platforms to argue that the economic future of the region or state could be greatly improved if expanded aid allowed needy residents to afford college tuition and fees and stick it out to complete their degrees.

- When legislation becomes possible, advocates of increased aid should aim to make it an entitlement to all financially needy students, not just one subgroup such as minorities.

Designing Successful State Aid Programs

Research in the social sciences suggests that programs gain broader support and prove more durable when the benefits are distributed widely. Targeting aid to all needy students, rather than minority students, delivers needed help to minorities in a way that also benefits others and builds broad citizen support. Furthermore, programs that automatically entitle all needy students to assistance can prove much more difficult to reverse politically, because such programs change expectations going forward for students, families, businesses and educational institutions in the state.

Over the past several decades, the wage return to Americans with college degrees has increased – yet the federal government is doing less to ensure access for financially needy students. States like California and Texas have stepped into this gap, as we have seen, and their experience reveals that educators and policymakers in many more states may soon be able to make the case for broad, need-based financial aid as a tool for building stronger economies in the future.