The City of Chicago, and the region more generally, suffer from extreme racial residential segregation. Despite the facts that 50 years have passed since housing discrimination became illegal, that the black middle class has expanded, and that whites’ racial attitudes have changed, Chicago remains one of the most racially segregated cities in the country.

Racial residential segregation has negative consequences for the health, well-being, and the social fabric of our city. Where you live impacts where you go to school, the jobs you have access to, the quality of your healthcare, your exposure to environmental hazards, your exposure to crime, the extent to which you accrue wealth, and many other factors. As such, racial residential segregation has been referred to as the ‘structural lynchpin’ that helps perpetuate racial inequality.

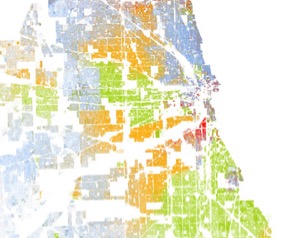

As illustrated in the 2010 Chicago regional map below, racial groups are segregated into different neighborhoods, with African Americans predominately on the south and west sides, whites to the north, and Latinos to the northwest and southwest. There are very few neighborhoods where all groups are represented.

Image Copyright, 2013, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin A. Cable, creator)

2010 Census Block Data one dot = one person; Blue=white; Green=black; Red=Asian; Orange=Latinx; Brown=Other/Native American/Multi-Racial

The True Causes of Segregation

A complicated web of economics, discrimination and preferences—along with social networks, lived experiences, and the media—shape how people come to live where they do. Although there is a common misperception that segregation exists because people prefer to live ‘among their own kind,’ there is a large body of rigorous research that clearly demonstrates that this is not true. Chicago’s segregation did not happen by accident. Local, state, and federal policies – alongside resident’s actions and reactions – embedded segregation in our city. The result is a self-perpetuating system of segregation, which negatively impacts our region and all of its residents.

Because of segregation, the impact of the housing boom—and subsequent bust—was felt more deeply by communities of color. In the early 2000s, black and Latinx homebuyers were targeted for subprime loans, even when their credit scores qualified them for less-risky mortgages. This concentrated foreclosures in Chicago’s communities of color, resulting in falling housing prices and vacant and abandoned properties. Tens of thousands of rental housing units in the city were also foreclosed, which left many south and west-side communities with substantial losses in affordable housing. Today, homeownership rates among black and Latinx Chicago area residents lag 20 percentage points below their white peers. And to make matters worse, the median property values for black and Latinx-owned houses are almost $100,000 less than those of white home owners (for further analysis see the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy report: A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report.

A recent study by the Urban Institute (2017) quantified the benefits of breaking this cycle of segregation. They found that a reduction in segregation would increase educational attainment for blacks and whites, with 80,000 more adults finishing Bachelor’s degrees. In addition, this study suggested less segregation would reduce the homicide rate by 30%, increase black per-capita income, and add $3.6 billion dollars to the region’s economy.

Given the many ways that segregation negatively impacts our city and its residents, mayoral candidates must consider a range of policies and initiatives to begin to systematically tackle the issue. Because segregation has many causes, there is no single policy solution. However, policy options do exist that can help us break this cycle of segregation.

Promising Paths Forward

- Mobility Programs. Housing Choice Voucher holders (also known as Section 8 recipients), low income people without Vouchers, the working class, and middle class people all make decisions about where to live based not only on economics, but also on their perceptions, experiences, and knowledge of their options in the city. Often the most readily available information funnels them toward segregated neighborhoods. Programs that open more doors and create more choices would help encourage moves that break the cycle of segregation.

-

For voucher holders, programs that encourage moves that break down segregation include: regional administration of vouchers; higher payment standards; security deposit assistance; counseling to support families through neighborhood transitions; housing search assistance; and connections to landlords. Research has shown that mobility programs with these features help low-income families make lasting moves to low-poverty and less-segregated communities. This can result in improved health outcomes for parents and educational and economic success for their children.

-

For the private housing market, policies that include counseling and community marketing that raise awareness about neighborhoods, break down stereotypes, and reduce barriers associated with housing searches would help. For decades, the Oak Park Regional Housing Center’s model has educated potential residents and successfully encouraged moves that advance integration. This model could be promoted for use in Chicago neighborhoods.

-

Affordable Housing. Although racial residential segregation is not driven solely by housing costs, there is an undeniable link between segregation and the availability of affordable housing. A recent report by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance provides evidence for the negative effects of Chicago’s “aldermanic prerogative” which allows an alderman to deny a request from a developer to build affordable housing in their ward. To help break the cycle of segregation, we need transparent planning policies that spread affordable housing throughout the city and region.

-

Investing in Places. In disinvested neighborhoods, infill development that replaces vacant lots with new and affordable housing can improve opportunities for residents and newcomers. Connecting economic development investments to neighborhood schools also can be beneficial. Experience suggests that involving community members in these processes is key. As neighborhoods experience physical and economic improvement, care must be taken to avoid displacement and preserve affordable housing. A wide range of programs should be considered, from tax credits for developers who provide subsidized housing, to mortgage assistance for low-income homebuyers. The Land Trust model, where land is owned by the community but housing is provided to individuals and families, can provide stability by mitigating against foreclosure and gentrification-related displacement pressures. For more on Community Land Trusts, see Shelterforce’s Organizing and the Community Land Trust Model.

-

Racial Equity Analysis. A promising policy option suggested by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance recommends the city of Chicago subject any proposed housing program or housing-related policy to a Racial Equity Impact Assessment. Similar to an Environmental Impact Analysis, any decisions related to housing should ask the question: what impact will this have on racial residential segregation in the city of Chicago? To predict the effect of any policies – even those with no explicit mention of race – on racial residential segregation will require careful deliberation about the systemic and institutional factors that created and perpetuate segregation in Chicago.